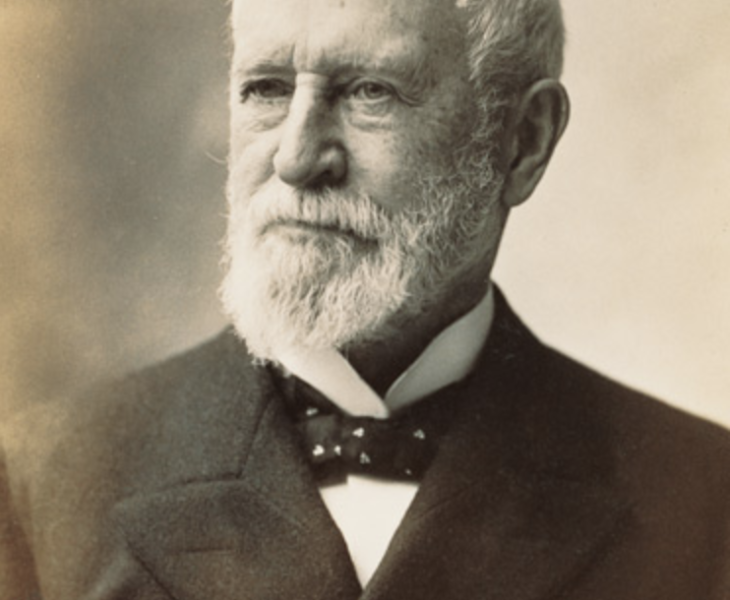

Behind the shimmer and renown of every Tiffany & Co. creation is a moving story of risk-taking, discovery and staunch dedication to quality and craftsmanship. It is also the story of the rise of American wealth and society, and how the ideal of luxury at the time was shaped in part by one man, Charles Lewis Tiffany (1812–1902).

Born in Killingly, Connecticut to a prosperous textile manufacturer, this visionary merchant was 25 years old when he and friend John B. Young—with $1,000 borrowed from Tiffany’s father—started a stationery and fancy goods store in New York City. Facing difficulties finding a suitable location that they could afford, with little knowledge of starting or operating a business and during the world economic depressions of the 19th century, Tiffany and Young prevailed. Their innately entrepreneurial spirit and inexhaustible work ethic allowed them to attain what few men could dream of doing in the 1830s, proudly opening the door to their emporium at Broadway and Warren Street on September 14, 1837. However humble the $4.98 in sales that the two recorded for the first three days in business, Tiffany and Young quickly began to prosper as New Yorkers vied for the merchants’ rare and exotic finds, including delicate Chinese porcelains and the latest French accessories. Mr. Tiffany outmaneuvered the competition by purchasing these coveted goods directly from ships returning to New York from foreign ports. With Charles Tiffany’s astute recognition of the importance of publicity, Tiffany quickly became an intrepid entrepreneur.

A most important year for the company in its infancy, 1841 saw the recruitment of another partner, Mr. J. L. Ellis, in what became a trio of astute businessmen. “Tiffany, Young & Ellis” was born. Then, with the fall of Louis Philippe’s regime in the 1840s, French aristocrats fleeing political turmoil became eager to exchange their diamonds for cash. Tiffany saw a golden buying opportunity and risked the profits of his fledgling enterprise on a cache of splendid diamonds, marking the first appearance of major gemstones in the U.S. The press took note and dubbed Mr. Tiffany the “King of Diamonds.” The incarnation of American luxury was beginning to take form.

Tiffany masterminded a second publicity coup in 1858 with the laying of the Atlantic telegraph cable. He bought 20 miles of extra cable from Cyrus W. Field, the project’s originator, and cut it into four-inch lengths finished with brass. Other parts were made into paperweights, canes, umbrella handles and watch charms. When the souvenirs became available for purchase, the crowds, vying for a piece of history, were so boisterous that the police arrived to contain them.

By the 1850s, the company was well on its way to becoming one of the world’s leading silversmiths. To meet society’s demand for silver goods, Charles Tiffany purchased the operation of prominent New York silversmith John C. Moore, which established the company’s silver manufacturing heritage. Moore crafted the silverware on par with English sterling—92.5% silver and 7.5% base metals—a standard that the United States eventually adopted and one that is still followed today. “925” sterling silver was accepted as the U.S. standard following Tiffany’s directive.

After both Young and Ellis retired in 1853, Charles Tiffany assumed control of the company and looked to expand the global reach and influence of Tiffany & Co. (its name having evolved from Tiffany & Young, to Tiffany, Young & Ellis, and finally, Tiffany & Co.). At the Paris World’s Fair of 1867, the company challenged European jewelers and received an award of merit for silver hollowware, the first time an American design house had been so honored by a foreign jury.

By 1853, Tiffany had expanded so much that it relocated to 550 Broadway in a five-story, purpose-built marble building, and remained there throughout the Civil War until 1861. At the center of the building’s entrance stood a nine-foot-tall bronze-coated wooden statue of Atlas clutching a clock—which still guards the entrance of the Fifth Avenue flagship store today.

A master merchant, Tiffany returned to New York to expand his emporiums, making room for a broader offering and even more lavish collections. In 1870, Tiffany & Co. relocated to its palatial Union Square environs. As motivated and enterprising as he had been in his youth, Tiffany galivanted around the city dressed in a cutaway coat and high silk hat. He always walked to work and never, in his long life, missed a day—even when he fell ill.

His openness to new ideas resulted in innovations that defined Tiffany’s, as well as America’s, sense of taste and style. One such innovation was the introduction of colored gemstones in fine jewelry. In 1876, Tiffany purchased an exceptional tourmaline from acclaimed gemologist George Frederick Kunz. Soon after, Dr. Kunz joined the company as its Chief Gemologist and collaborated with Charles Tiffany in sourcing the finest gemstones in America and the world for Tiffany’s clientele.

In 1877, one of the world’s largest and finest fancy yellow diamonds was discovered in the Kimberley diamond mines of South Africa. Charles Tiffany purchased the behemoth 287.42-carat rough stone for $18,000. Under the guidance of Dr. Kunz, the diamond was cut into a cushion-shaped brilliant weighing 128.54 carats with a then unprecedented 82 facets, creating a gem that sparkled as if lit by an inner flame. The Tiffany Diamond, as it is famously known, set a company precedent of cutting for beauty rather than size, a standard Tiffany & Co. maintains today.

One of the greatest tributes to Charles Tiffany’s pursuit of excellence is the unprecedented recognition the company received at the great world’s fairs. At the 1878 Paris fair, Tiffany received the top awards for silver and jewelry, and Charles Tiffany was awarded the Cross of Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur. As a result of these achievements, Tiffany & Co. became the imperial jeweler and royal jeweler to the crowned heads of Europe, as well as the Ottoman emperor, the czar and czarina of Russia and the shah of Iran. At the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1889, Tiffany again received a grand prize for silverware and a gold medal for a spectacular collection of bejeweled orchid brooches that were praised by the judges and the press for their lifelike quality.

In the last 30 years of the 19th century, Tiffany & Co. was the premier source for the luxuries and unlimited extravagance that defined the Gilded Age, which was fueled by the fortunes created during the Industrial Revolution. Prominent American families, including the Goulds, Astors, Vanderbilts, Havemeyers and Whitneys, as well as the era’s leading artists and politicians, came to Tiffany & Co. for their invitations, silver tableware, custom flatware and dazzling jewels. Tiffany also created the magnificent trophies that captured the pageantry of the great yacht and thoroughbred horse races of the period.

While Charles Tiffany built his company into the first institution of American luxury, his son and heir to the business, Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933), forged his own path to the pinnacle of American design. Recognized as the leading American designer working in the Art Nouveau style, Louis Comfort Tiffany celebrated nature and exotic cultures in his iconic designs for stained glass lamps, pottery, bronze ware and jewelry that shaped the younger Tiffany’s legacy as a distinguished American artist.

Louis Comfort Tiffany was appointed design director at the death of his father in 1902. Charles Tiffany left an estate of $35 million—nearly $1 billion today—but his most lasting achievement is the founding of Tiffany & Co., the American luxury institution that will forever epitomize superlative quality, cutting-edge innovation, discovery and legendary style.

TIFFANY, TIFFANY & CO. and T&CO., amongst other names and symbols, are trademarks of Tiffany and Company and its affiliates. © 2021 Tiffany and Company. All Rights Reserved.